The

Brannigan Outrage

Throughout

these Misadventures,

Mike Brannigan has been a bad man—violent, petty, and lacking in

scruples. With this chapter, he will make the step from unlikeable

anti-hero to outright villain. To counteract the villainous Mike

Brannigan, let us introduce a protagonist—the pioneering frontier

actress Edith Mitchell.

|

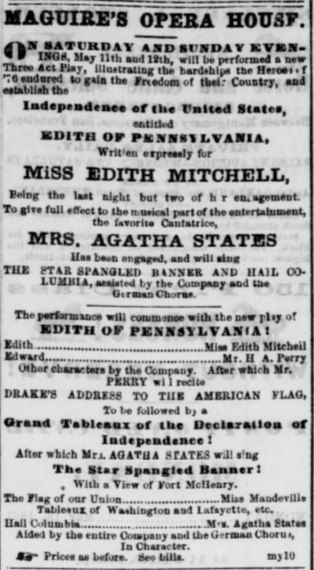

| Patriotism was on the playbill when Edith Mitchell headlined at Maguire's Opera House during the first months of the Civil War. From the Daily Alta California, May 11, 1861 (California Digital Newspaper Collection) |

(Read Part 8: The Worst Cabdriver in Sacramento)

Though often billed

as “The Great American Tragedienne,” Edith Mitchell was born in

London in 1834. Emigrating to the States at a young age with her theatrical family, she married a fellow expatriate English actor, William

Melmoth Ward, who, though once a handsome leading man, had by 1852

become notable for his “heaviness and abdominal prominence,” in

the words of a theater gossip columnist. When Edith headed west, her

husband appears to have stayed in New York, and soon disappears from

her story. Edith always used her maiden name on the stage.

|

| The great Charlotte Cushman as Meg Merrilies. Edith's first big break was as Cushman's understudy in this role. (Wikipedia) |

Edith began her acting career in Buffalo and in New York City. Raven-locked, and armed with a powerful contralto voice, she was drawn to melodramatic roles such as Lucrezia Borgia, the gypsy woman Meg Merrilies from Guy Mannering, and the vengeful and tragic Lionne from The Doom of Deville—a part which she claimed had been written expressly for her. One critic noted approvingly that, in addition to acting ability, Edith had "external advantages in her favor."

About 1858 she started travelling the West. For the next few years she appeared onstage in several Western cities, including Chicago (where she was indifferently received), Milwaukee (where she was a smash hit), St. Louis (where she fired her manager for attempting to steal her $70 watch), and Louisville (where she “gained many admirers”). In April of 1861 she arrived in San Francisco, and headlined for seven weeks, first at Maguire’s Opera House, then at the American Theatre.

|

| A pro-Union rally at Post and Market streets in early 1861, during the outbreak of the Civil War. (San Francisco Public Library) |

It was an exciting

spring. The Civil War had just begun, and Californians received

updates on Eastern developments via the Pony Express. Patriotic,

pro-Union sentiment was widespread, and one vocal supporter of the

Confederacy had to flee town after being burned in effigy.

Accordingly, San

Francisco’s theaters rose to the occasion with patriotic fare. One

of Edith’s first performances at Maguire’s was as the star of

Edith of Pennsylvania, a Revolutionary War drama written

expressly for the occasion, accompanied with patriotic songs and

speeches, and “a Grand Tableau of the Declaration of Independence.”

During her seven weeks on the San Francisco stage, Edith also

performed the pro-Temperance play, Ten Nights In A Bar-Room,

headlined the tragedy Evadne, and of course starred in her

reliable “sensation drama,” Doom of Deville.

Reviewers tended to

emphasize the forcefulness of her performance. The Alta

stated:

A large audience was in attendance at the second representation of the “Doom of Deville” last evening. The piece, though long, has many redeeming features, and some of the scenes are truly ludicrous in the extreme. ... Lionne is finely managed by Miss Mitchell, and her impassioned portrayal won warm and frequent applause. The part is very heavy, and requires strength and great elocutionary powers to sustain it successfully to the close.

The Bulletin

opined that:

Unhappily, her figure is too stout to be very graceful on the boards; yet she possesses a strong, full toned voice, and recites very well.

In the opinion of

the Golden Era,

Her intensity at times, ‘tis true, approximates to raving—an error into which she is betrayed by superabundant vitality, we should say, rather than lack of judgment.

Edith’s

“superabundant vitality” was a necessary quality for a single

woman in her twenties traveling the Western frontier. Apparently,

Mike Brannigan was drawn to such strong, independent women, often with

bad consequences. On the one hand, he was a close friend of Belle Cora, the tragic San

Francisco madame, who had even given Mike some of her late husband's clothes when Brannigan had been exiled from San Francisco by the Vigilance Committee. On the other hand, when Frances Willis stood up to Mike, he had

struck her across the face with a horse-whip.

|

| Steamships departing for Sacramento from the San Francisco waterfront, 1860s. (Online Archive of California) |

On June 22, Edith

took the river steamer up to Sacramento, to begin a run at the

Metropolitan Theater. Mike Brannigan met her at the docks and took

her in his elegant carriage to her rooms at the St. George. The next

day was a Sunday; when Edith descended the stairs of the hotel she

found Mike waiting for her. The Sacramento Bee reported their

conversation as follows:

Mike ... said, ‘Madame, while you are in this city my carriage is ever at your disposal. Would you not like to take a drive this afternoon?’

Miss Mitchell replied, ‘No, sir, it is too warm to-day.’

‘Perhaps you don’t remember me,’ said Mike; ‘I am the gentleman who drove you up from the boat last night.’

‘Ah, indeed, sir, you were very kind; but I did not pay you.’

Miss Mitchell here made a motion to take out her purse, when the hack driver interposed, ‘There is nothing to pay, madame. While you are in Sacramento my carriage is at your disposal, free of charge. All the actresses patronize my carriage, and I used to drive out Mrs. Hayne, Miss Hodson, and all the rest of them.’

Mike could be

charming when he wished, and Edith eventually agreed to go out

riding, as long as she could bring along two older women as

chaperones. They spent the afternoon at Smith’s Gardens, a nursery

and pleasure resort just outside of town, then stopped off for food

and drinks at the Tivoli House on the way home. Here Edith noticed a

funny taste in her beer—not mistakenly, as Mike had mixed it with

brandy. She was suspicious enough to order another bottle which she

poured herself.

Come evening, Mike

had drunk too much to drive home, so two of his hired drivers rode

out in a second carriage. Edith and her chaperones piled into the new

carriage to head back to the St. George, while Mike climbed into the

back of the other one. Mike called for Edith to come to his carriage

and ride back with him; after a few minutes she complied. The

carriages headed out in different directions. Along the way, Edith

passed out, and Mike raped her.

About four in the

morning, Edith woke up in bed in a strange house with Mike getting

dressed next to her. Her arms and legs were covered with bruises.

After she passed out again, Mike left and spent the morning bragging

to various low-life friends about his conquest.

She woke again

around seven, and made her way into the street. In addition to what

she had already suffered, her situation was bleak. The cultural

double standard regarding rape, which still persists to this day, was

all the stronger back in 1861. For a public figure like Edith

Mitchell, being the victim of rape could be devastating to her

career. Brannigan was certainly counting on Edith to be broken by the

experience, and to crawl back to San Francisco in shame. When she

returned to the St. George, the management informed her that, due to

her disreputable conduct over the night, she would have to seek other

accomodations.

But Edith was tough,

and she stood her ground. Summoning the police and a lawyer, J.W. Coffroth, she bravely gave her account of the night’s events. The

police set up a search for Mike; and the hotel manager backtracked on

expelling Edith, instead announcing that Mike Brannigan was no longer

welcome on the premises of the St. George Hotel. After delivering

statements to the police and reporters, Edith rested briefly and

then, despite everything, went to the Metropolitan Theater and

performed that very evening as Lionne in The Doom of Deville.

As word of the

outrage spread on the street, Mike Brannigan wisely dropped out of

sight. Anger spread through Sacramento like wildfire, and there was

talk of lynching Brannigan if he could be found. Luckily for Mike,

the police found him first, hiding in a stable, and clapped him

safely in jail.

Through prompt,

decisive action, and sheer strength of character, Edith Mitchell was

able to prevent the rape from becoming a blight on her career. She

finished her tour of Sacramento to high acclaim. The next year, she

again headlined at San Francisco’s leading theaters, then toured

Canada. In 1864 she decided to set off across the Pacific. While

waiting for a ship to Honolulu, she gave what is remembered today as

the first performance of Shakespeare in Seattle, a dramatic reading

in which Edith played all the parts, “being the whole troupe

herself.”

|

| Advertisement from The Argus (Melbourne, Australia) of August 15, 1865. (National Library of Australia) |

From Hawaii, Edith

traveled on to Australia, headlining in Melbourne and Sydney (where she was panned by critics), and Adelaide (where she was a smash hit). Drawn yet again to the frontier, she traveled further

West, where Edith and her colleague Annie Hill became the

first professional women thespians to tour Western Australia.

Still seeking

adventure, Edith continued her journey, setting off from Perth to

India, intending perhaps to circle the globe. In India she toured Calcutta, Bombay, and the North-Western Provinces, but while en route to Ahmedabad she fell

sick of dysentery. The American press barely noticed her death on

January 2, 1868, at the age of 34.

And what of Mike

Brannigan?

Once again, Mike

gained access to a crack team of lawyers who were able to delay the

case for month after month. In the meantime, Mike remained locked up

in jail since, having lost his business, he had trouble making

bail—or perhaps he was unwilling to post bail, seeing as Edith

Mitchell’s father was rumored to be waiting for him with a pair of

derringers.

|

| J Street and the St. George Hotel during the Great Flood of 1861-2. (Sacramento Public Library) |

In January of 1862,

as Sacramento was ravaged by devastating floods, Mike’s case

finally came to trial. He was defended by the great pioneer defense

attorney, Col. G.F. James, who had also argued Mike’s defense in

the Frances Willis case. The defense made almost no attempt to argue

that Mike was innocent, instead drawing up a long list of

irregularities and technicalities to get the case thrown out. The

judges were not convinced, and the jury returned a verdict of guilty

as charged.

On January 30, 1862,

the gates of San Quentin shut behind prisoner 2308—Mike Brannigan,

convicted to a sentence of ten years.

Exactly one year

later, he was free.

(Next time: Escape from San Quentin!)

|

| Advertisement from Perth Gazette and West Australia Times, September 15, 1865. (National Library of Australia) |